Policy positions

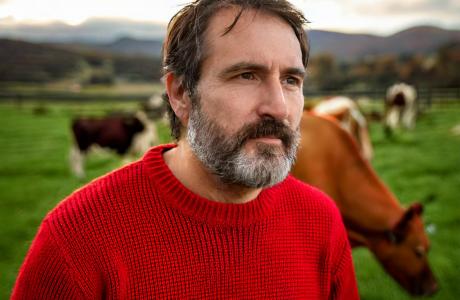

Policy position 1

Living from nature

Nature is a resource. It provides sufficient resources for human livelihoods, needs and wants. It contributes to and provides everything human societies need to thrive and prosper. In this view, humans have a right to use plants, animals and minerals to survive and to make things they need, such as food, clothing and shelter.

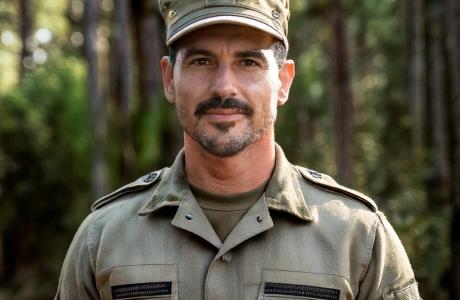

Policy position 2

Living with nature

Nature exists for both human and non-human beings. Nature provides for the needs of all organisms. In this context, people use natural resources carefully, are responsible towards nature and take measures to protect the environment so that both humans and nature can thrive together.

Policy position 3

Living in nature

Nature is land and landscapes. Natural sites and places are important for people's lives, culture and practices. A particular natural area contributes to making a human society what it is. In this view, people see themselves as part of the natural world and do their best to keep it healthy.

Policy position 4

Living as nature

Humans are part of nature. People feel connected to nature physically, mentally or spiritually, nature is a part of them. In this context, people understand that they are interdependent with nature and that everything they do affects the environment. They feel a deep connection with all living things, such as animals, plants and even air and water.